Writing Is Like An Exoskeleton For The Brain

The human brain is both incredibly powerful and very limited. A simple pen can help you make the most of it.

An exoskeleton is a wearable machine aimed at enhancing the possibilities of the body. It increases the strength of the person wearing it, by adding external power to human power.

In pop culture, the most famous exoskeleton is the Iron Man armor.

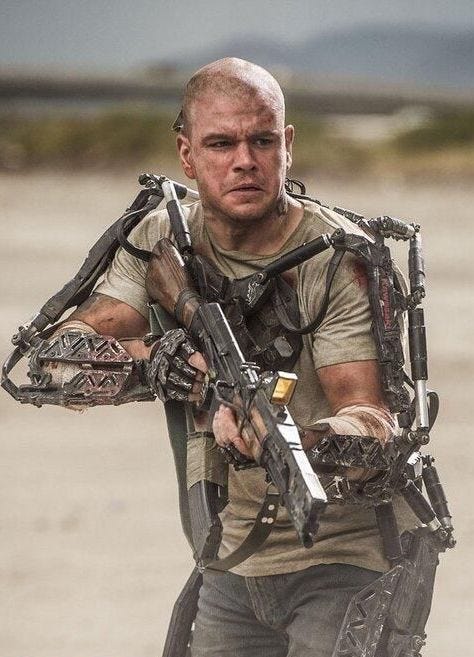

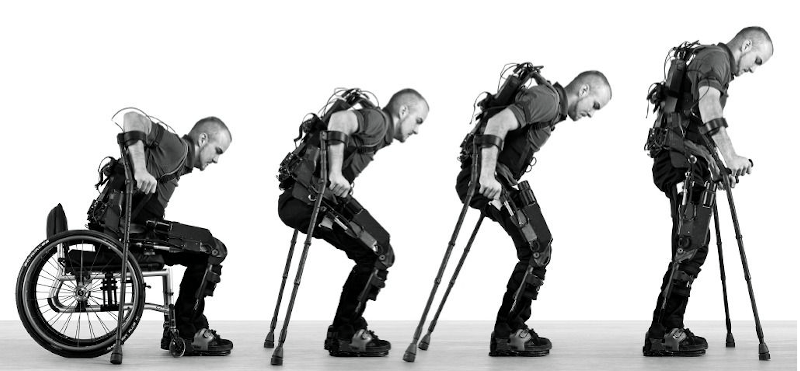

But this exoskeleton is so sophisticated that the result looks like a robot, not like an enhanced human. A more interesting exoskeleton can be seen in the movie Elysium.

This exoskeleton makes it easier to understand how it’s enhancing (not replacing) the body. It turns out this lightweight version is also more realistic — very similar ones are being explored to help people with disabilities gain autonomy.

Now that we’re clear on what an exoskeleton is: did you ever wonder what an exoskeleton for the brain would look like?

It turns out it looks like… a pen. Because, when practiced with rigor and regularity, writing is like an exoskeleton for the brain.

Is that idea counterintuitive to you? You have probably developed a misconception about the purpose of writing. In school, we are implicitly taught that writing is there to produce a proof of knowledge to a teacher. Then at work, we mostly rely on writing as a way to communicate information to a colleague.

But writing can be so much more, once you stop considering that it is only useful for the reader. Our own brain is incredibly powerful, and also highly limited. Those limits can be lifted through writing, exactly like an exoskeleton pushes the boundaries of the human body.

Here are the numerous ways you can turn writing into an exoskeleton for your brain.

Writing to sharpen your gaze

As soon as you start writing regularly, something weird happens in your life — you see things that you didn’t pay attention to before.

It is as if, knowing that there was now a recipient for this purpose, your brain was allowing itself to observe things more thoroughly. Specific details rise to the surface and resonate more strongly. A word. A gesture. A feeling. A question. A pattern.

The first step is to take notes. Whatever catches your attention is worth jotting down. You don’t need to know on the spot what you will do with these notes — that will become obvious, later.

Writing to discover your thoughts

Expert writers don’t try to put their thoughts in writing. It’s the opposite that happens. They discover what their thoughts could be by writing. Now, it’s not a mystical phenomenon — those thoughts are already somewhere in you. But you are unable to think about them, or to formulate them, without going through the writing step.

It's a funny phenomenon to experience. You pay attention to something that strikes you as interesting, you try to put into words this vague impression you have, and you find yourself unfolding, word after word, an observation that is much richer than the initial insight that got you started.

After going down that path again and again, and seeing how what you ended up writing is systematically better than what you wanted to write about, you get into the habit of writing, just to know what you are thinking.

Writing to develop complex rationale

Some thoughts are too complicated to fit into your brain. Your brain just doesn’t have the ability to memorize the beginning of a thread, the long and messy development of it, and the logical conclusion that comes out of it.

The best way to avoid this is to increase the capacity of your brain. Here, in this case, it is the working memory that you are missing. With a larger working memory, you are able to pursue complex rationale without losing key things to keep in mind along the way. The writing serves as an external hard drive.

If everything you need to remember is stored outside your brain, you can devote all of brain’s capacity to playing with the elements there, rather than having to waste some of it to temporarily store them.

Writing to think against yourself

Your brain is very good at applying a veneer of clarity to the half-formed ideas that pass by. When thinking about them, you have the impression that you understand them.

Then someone asks you a simple question about the topic, or opposes a new argument to yours, and you respond with a blank stare. The veneer cracks, and you are surprised that there’s nothing under it.

Discovering that you don’t understand something doesn’t have to happen in this embarrassing manner. When you write about a topic, you quickly spot the holes in your thinking. Somehow, once the writing is out, you can look at it as something external, which makes it easier to look at it with a critical eye.

Writing to find the essence

Remove a word. And another one. Replace an acronym by its full version. Discover that some interesting ideas you included don’t fit in there. Kill a darling. Rewrite a sentence to make it a bit clearer. Add an example, to make it less abstract. Read the whole thing, and realize an entire paragraph could be erased without seeing the whole thing collapse. Find a more common word. Double check a reference to see if you could simplify a part while keeping it accurate. Break a long sentence into two shorter ones — and end up deleting the second one, too redundant.

By giving you the ability to edit your words, writing lets you refine the expression of your thoughts in a way that thinking or talking doesn’t allow.

When you are done with this editing process, you reach the essence of your thoughts.

It’s clear, it’s sharp, it’s dense. It’s the refined version of your initial idea.

Writing to solidify your memories

To remember something, you need three events: a moment of attention (you experience something), a moment of consolidation (you anchor what you have experienced in your long-term memory), and a moment of restitution (you fetch the stored memory and bring it to the surface of your consciousness).

If the habit of writing amplifies your attention level, it also improves the consolidation process. Reflecting on moments you experienced increases the likelihood that you will remember those moments. And connecting those events with previous memories already stored will give you more entry points to retrieve those memories later on.

Writing to speak with more fluidity

When someone asks you a question about a topic you have written on, your answer is more structured.

You are still improvising on the fly what you’re saying, but the many benefits of writing shared above come together and feed your mouth.

Your brain is able to rapidly retrieve relevant pieces of writing that contain complex elements of rationale boiled down to their essence. You don’t even realize that it’s happening. What you do observe, though, is that you are more confident with your answers.

Complex rationale + clear thinking + solid memories = fluid speech.

Writing to stop thinking

An active brain can be a gift as much as a curse. Incredibly useful, but also exhausting at times.

To reduce this side effect, writing can be an incredibly effective method. Because one great consequence of putting your thoughts down is the inner silence that follows. The brain slows down a bit, stops clinging to the last idea that came by. If you are lucky, the brain even goes so far as taking a short break, surprised that there is nothing more to chew on.

Somehow, the effects are similar to a meditation process. It’s the off button that you didn't know of.

30 years ago, to explain how computers would open up an entirely new range of capabilities for humans, Steve Jobs described them as a bicycle for the mind. He was absolutely right about the unlimited possibilities of computers. What he may have underestimated was how much a machine that powerful can override the brain it is suppose to help. The latest generation of tiny computers, that ones that fit in our hand and hypnotize our eyes, seem to be taking over our brains as much as they are enhancing it.

In comparison to a computer, a pen is a modest exoskeleton. It’s also a more controllable one.

Start writing.

Every two weeks, I write an article to explain how the mind works, usually through a comparison that everyone can relate to.

You can subscribe to receive those articles in your mailbox — just enter your email below.